In our earlier posts we explored two key elements of successful exit preparation: the overarching idea of preparing to be “bought not sold” and the “essential actions” a company and board can undertake, well in advance of any planned exit, to maximise both price and certainty. A third vital dimension in any successful exit prep phase (what we term “Stage 1”) is cultivating serious buyer interest well in advance of an intensive exit process (“Stage 2”).

Defining a “Real” Buyer Group

Before a company can develop serious buyer interest, it needs to identify who those buyers are. This is far easier said than done. In some cases, the best buyers are already obvious. But more often the eventual buyer could emerge from one of several directions. We would argue that creating a list of even 50-100 companies that could have an interest in acquiring a business is not being comprehensive, it is being lazy.

The real challenge lies in prioritising the best or most likely buyers, allowing advisors to focus their and management’s time where it will yield the highest ROI. Just as it is often harder to write a one-page summary than five, so filtering is a process that typically requires time, exploration and patience to execute well. It is ideally suited as a key step during any 6–18-month Stage 1 exit prep process.

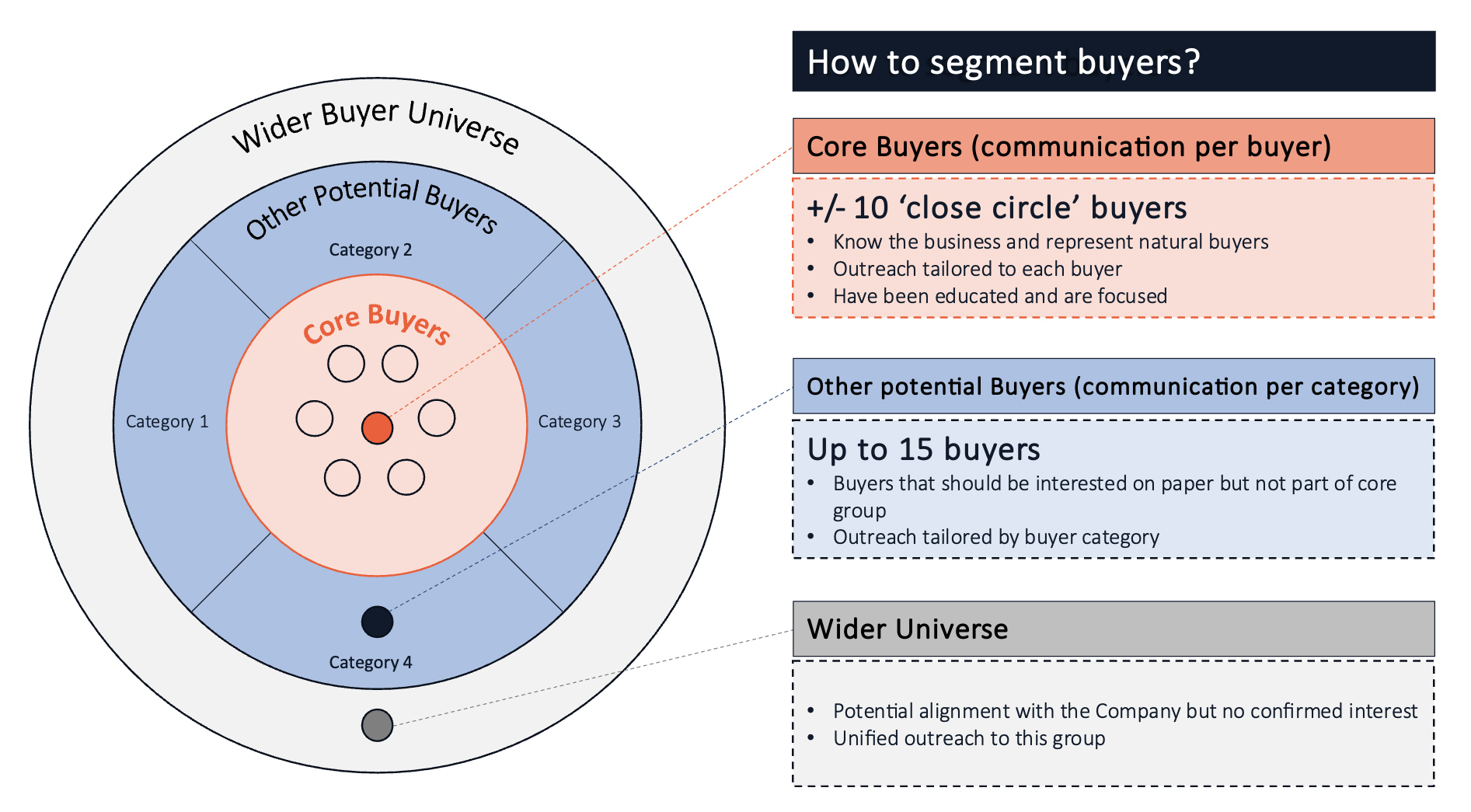

To help companies think about that process, we often use the following schematic:

At the centre is a very small group of “core buyers” who already know the business, may compete directly, or have made overtures in the past. Rarely does that number exceed ten, even in the hottest sectors. Beyond this group we ‘force’ ourselves and our clients to segment the remainder into two quite different containers.

The first comprises buyers in logical categories (“Other Potential Buyers”). For example, for an HR incentives business one category would be HR software buyers lacking fully developed incentive offerings. In the case of a payment fraud software company, it might be a group of payments buyers without deep fraud expertise. The list of such adjacencies is endless, but it should illustrate the thought process involved.

The second additional grouping we call the “Wider Buyer Universe” which includes a whole range of buyers that ‘could’ or perhaps even ‘should’ be interested but remain untested and are therefore more speculative. For instance, a company achieving surprising success in Japan might consider buyers based there who could immediately multiply its presence. A data centre tools company may consider one or more global data centre operators as a possible group, even if they aren’t focused on software. A fuel cell technology start-up may look to established hydrogen technology platforms who seek to consolidate local niche technologies to scale across their existing global network. The list is, by definition, near endless. What is most important is the thought process: filtering, focus and prioritisation.

The aim of this approach is to avoid the ‘laundry list’ method of creating a buyer universe and compels us and our client’s team to really think about each type of buyer, their perspective and how they might view such an acquisition. As illustrated on the chart above, it also naturally establishes the most effective communication strategy for each ‘ring’ of buyers. In the innermost ring, it is imperative to deliver very buyer-specific information from the outset, defining exact points of leverage. In the second ring, one needs to tailor the outreach by category with different sets of key points depending on which category each buyer operates in. Finally, in the third ring, there is a much broader canvassing for potential interest, with the expectation of a low hit-rate.

In our experience over 90% of eventual buyers come from one of the two innermost rings. However, occasionally, but still often-enough, a truly ‘left-field’ buyer emerges from a broader canvassing, with the rationale only becoming apparent after the fact. In fact, that is one of the benefits of Stage 1: potential buyer exploration without the time pressure of a bid deadline. Frequently, this ‘left field’ buyer interest is driven by an internal issue or challenge faced that no sale process can identify in advance. Naturally, broad canvassing comes at a clear cost in terms of overall market exposure for company, so that cost needs to be weighed against the potential incremental benefit on a case-by-case basis.

Cultivating vs Contacting Buyers

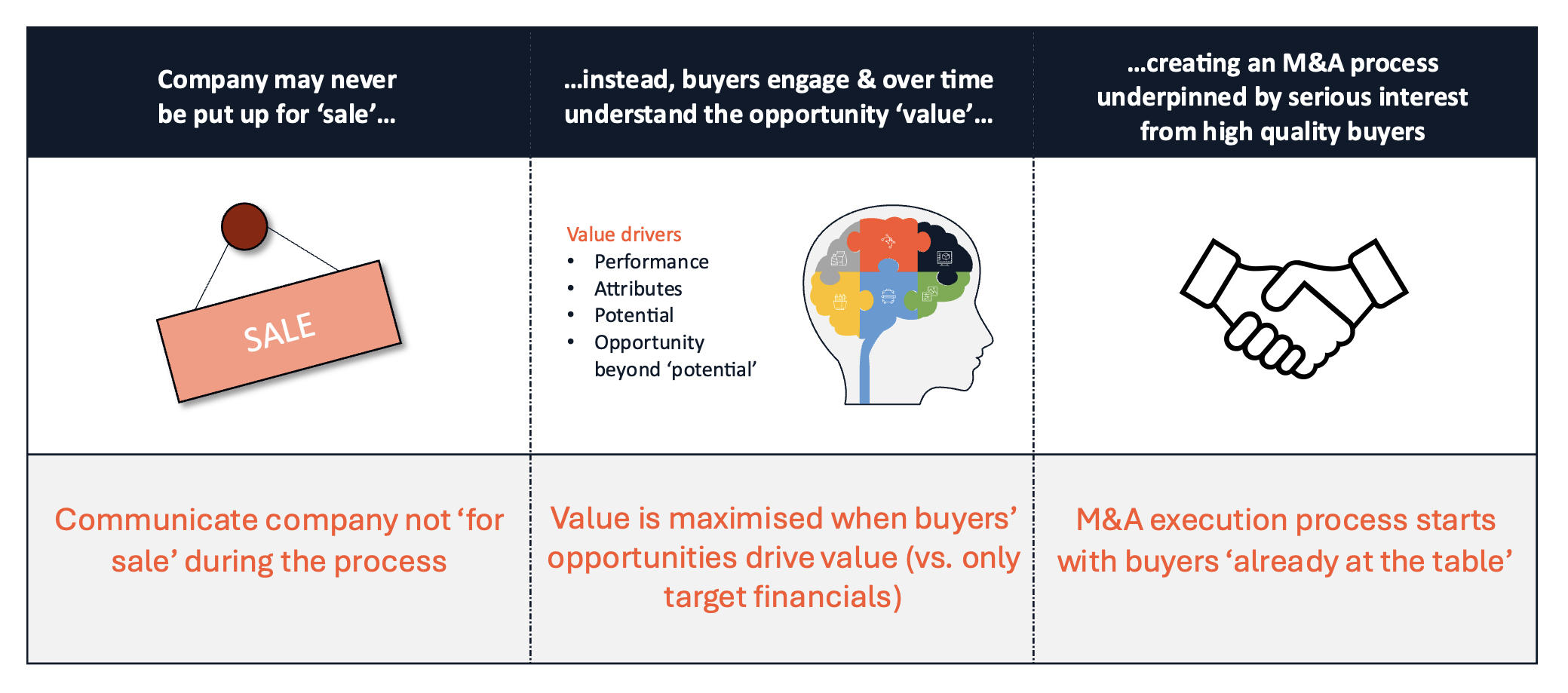

The next step is cultivating buyer interest from the various categories. Nearly any networked board or investment bank can access a wide range of potential buyers. In fact, today this is easier than ever. Experienced acquisitive buyers have built large teams who actively seek out potential targets and stand ready to evaluate attractive acquisitions; when reaching out to buyers, you are pushing on an open door. However, there is a fundamental difference between that effort and true buyer cultivation. Buyer cultivation is rooted in two fundamental principles: a) buyers need to be able to ‘see’ the full opportunity an acquisition can deliver to them, rather than simply being presented with an asset for sale, and b) the merit of an acquisition needs to be or become their idea, not yours.

This second point is truly fundamental to the entire approach. The simple, yet largely ignored, truism is that to maximise price and certainty, multiple buyers need to ‘want’ and even ‘need’ to acquire a company. When buyers are cultivated to the point where they are the ones pushing for a deal, a company and its board can be certain their market-testing exercise will yield the maximum benefit. At the same time, it is important to recognise upfront that cultivating any buyer to that point takes time and effort. Actively prioritising a small group of buyers who we and our clients believe will really ‘get to the finish line’ is a core part of this exercise succeeding.

So, how does a company cultivate, rather than pitch, to buyers to the point where they are the ones pushing for a deal? There are several dimensions to the answer:

- It is critical to understand specific buyers’ objectives, the problem(s) they are trying to solve and their internal timelines. Most companies and advisors don’t ask many questions; everyone is too busy pitching, making sure to land all their key points before the Zoom call ends. But in fact, most strategic buyers are happy to explain their requirements, their issues, and what their ‘hot buttons’ are for a deal – if you just ask. For example, a buyer’s business unit may be behind its growth forecasts and ‘need’ to acquire, the company may have stated publicly it will achieve X and isn’t close enough yet, a buyer may be having great difficulty recruiting core talent that would automatically come with an acquisition, etc. The point is to turn engagement from a pitch to a discussion and understand clearly why the buyer is on the call.

- A closely related point is understanding strategic fit from ‘the other side of the table.’ Corporate development teams focus on leveraging their existing market positions, product roadmaps, sales channels and customer relationships. Rarely is an acquisition a ‘blank slate’ deal that moves a buyer into a completely new segment or model built entirely around a target. In 99% of cases, it is the reverse; an acquired company must fit into an existing set of objectives and requirements. We would strongly argue that probing, defining and aligning those requirements with what a target can deliver post-deal is NOT the job solely of the acquirer’s team. In fact, a near-certain route to a higher exit value is for the target company and its advisors to be proactive in articulating those benefits. In many cases, after gaining a deep-enough understanding of a buyer’s requirements, we create slides on the benefits of a transaction which are shared with both sides. Parts of those slides are regularly reused by buyers internally in making their case. Taking the lead on this sort of ‘synergy’ discussion closes a deal faster, and at better terms, than simply setting a bid deadline and evaluating offers. The core reason: buyers pay maximum price when they fully appreciate the opportunity, not just the company’s current attributes. The easier we can make that process for a buyer, the better the outcome in price or certainty, or both.

- Sell to ‘everyone’ at a serious buyer – the adage that people, not companies, do acquisitions is an adage for good reason. Large buyers have many different groups looking at a deal: corporate development, business unit leaders, strategy departments, and legal/compliance to name a few. Nearly always these groups are ‘technical’ rather than ‘economic’ buyers, meaning they aren’t significant shareholders in the buyer and therefore do not directly benefit economically from future success. What these different teams most often seek is fit, risk-reduction and resilience. Whilst it is largely true that, in the end, one or two senior people need to ‘own’ any acquisition, a deal doesn’t close without sign-off from multiple parties. A core part of our advisory job is helping companies navigate those constituencies. A good example that recurs often is the ‘conflict’ between acquiring or building in-house; many buyers’ product teams will claim ‘give us enough time and money and we can build this.’ What is important in these cases is to anchor the value of time-to-market (an acquisition delivers that product day-one), certainty (the product is already built, so risk-free), and competitive value (you can offer this before your competitors can). That kind of ‘triage’ can only be done by marketing the opportunity to different groups WITHIN key buyers to maximise the chance that one group doesn’t veto a deal for their own, entirely understandable, reasons. This takes time and work and is precisely what Stage 1 enables that a standard sale process cannot achieve.

- Understand how different buyers will value an acquisition – Some buyers will focus only on certain aspects of a company’s business. Others have valuation templates which they must fit every acquisition into. As one example, many buyers use discounted cash flow analysis as one approach to value acquisitions. These analyses use the buyer’s internal cost of capital, which often they are happy to share or at least describe. Armed with this knowledge, the company already has a very good idea of the forecasts and assumptions that will lead to an attractive exit price. It doesn’t mean any company can simply convince a buyer to pay X by knowing this, but it does provide a clear roadmap to what a buyer needs to believe to pay X, which is already very valuable if for no other reason than to clarify the probability buyer and seller can land on an acceptable price. Another common approach used by most sellers is to focus on multiples (of both forward and historic revenue or EBITDA). That insight alone can help focus both sides on the right parameters to discuss and highlight.

- Where it makes sense, buyer engagement in Stage 1 can start with engaging in commercial partnership discussions. To be clear, the objective of Stage 1 is to catalyse an exit process, not just build out a company’s strategic partnership network. However, we find that in certain cases starting a commercial discussion, in the framework of evaluating a potential eventual deal, is an excellent way to build familiarity and confidence to acquire. Many times, buyers already in partnership discussions in Stage 1 move quickly to deal-mode when Stage 2 is triggered more broadly, those earlier discussions being effectively a form of advance commercial due diligence.

All the above takes time, so the natural question is how best to fit this within 10-15% of a CEO’s time (the target for a successful Stage 1)? There are a few steps that make sense:

- Broad initial qualification –the umbrella that the company is not for sale but will exit in the near to medium term (so a buyer is not wasting their time considering it) enables time to understand real potential interest and desire.

- More specific qualification of a sub-group of potential buyers and ‘get to know each other’ discussions between senior teams. This is always done two-way; a target is probing and asking as many questions as the buyer team, not pitching a story for 45 minutes straight.

- More specific action plans developed with an even smaller subset of potential buyers, which often includes multiple stakeholder discussions, specific evaluations (for example, a discussion on go-to-market opportunities post deal) or starting a commercial partnership discussion.

- The above naturally leads to deeper engagement with a handful of potential buyers.

- It is critical these actions happen in parallel with awareness of the company building as discussed in our previous post; the two stages work together with Stage 1 being a holistic approach to building momentum towards a sale process, not just a series of one-off ‘fireside chats’ with buyers.

What is the goal of all the above? To create interest amongst a few potential buyers who are truly ‘at the table’ before a Stage 2 exit execution process starts. This is the exact opposite of sending a ‘teaser’ to 70+ parties to canvas interest. Having even 3-4 buyers seriously at the table, understanding the opportunity fully and ready to engage to do a deal is, in our experience, worth far more than any intensive, wide marketing process. In its essence, the goal should be to qualify a range of buyers, then to go deeper with a smaller group, rather than wider with dozens. Having even 2-3 buyers competing head-to-head to make sure they acquire a company in our experience, across 300+ deals, delivers higher prices and greater certainty than a dozen ‘buyers’ looking at documents in a data room with a bid deadline looming.

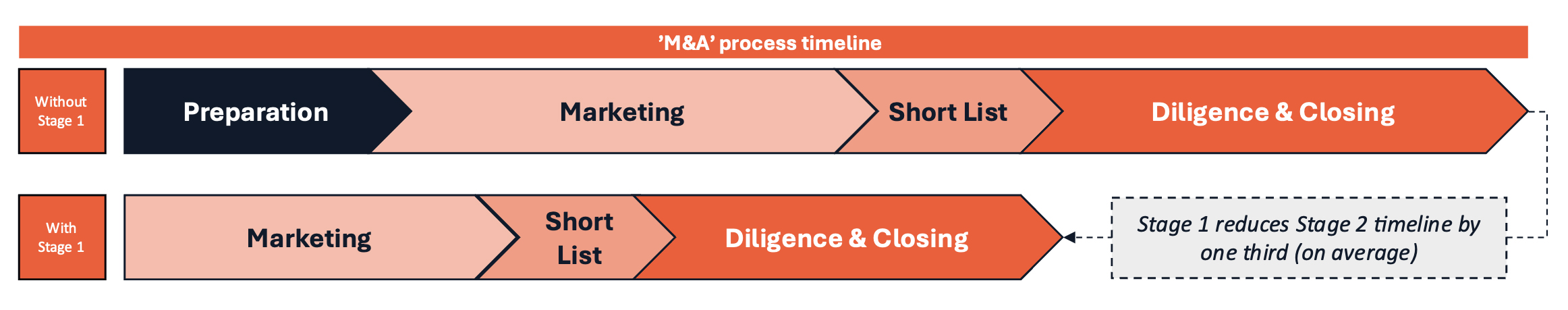

This stage 1 step also delivers a much faster, more certain Stage 2. In our experience, companies can shave months off a formal deal process, recouping much of the time spent on preparation. The following schema outlines the proven time savings in Stage 2 with the benefit of Stage 1:

Being ‘bought, not sold’ requires a fair amount of ‘marketing’ in Stage 1

- Thoughtful exit preparation for 6-18 months before a formal exit process consistently yields higher prices and greater certainty

- Consider it as the ‘marketing’ phase preceding the ‘selling’ phase of a successful exit

- A core element is articulating and communicating the opportunity a company presents, beyond merely its ‘asset features’

- Another is prioritising key buyers, taking time to understand their requirements and timelines, and marketing thoughtfully into those

- Broadcasting the opportunity in various ways to different buyer constituencies takes time, and can only be accomplished during a structured Stage 1

- The whole objective of Stage 1 is to move into an intensive, competitive Stage 2 where buyers are competing to close a deal and a company is truly being ‘bought not sold’:

We firmly believe that staging the exit process into two distinct phases, aligning internally and externally on the key value drivers, and cultivating buyers consistently delivers better outcomes for management, investors and other stakeholders across nearly every growth sector. Put simply, this is a better approach to achieving great exit outcomes.

We firmly believe that staging the exit process into two distinct phases, aligning internally and externally on the key value drivers, and cultivating buyers consistently delivers better outcomes for management, investors and other stakeholders across nearly every growth sector. Put simply, this is a better approach to achieving great exit outcomes.

Learn more about us.

View our transactions.